January 31, 2020

Parts of this document contain detailed discussion in addition to instructions. These details are for reference only - something you can use if/when you later revisit this tutorial. During the workshop, this author will engage in discussion and provide verbal instructions. You will primarily use this guide for the R syntax (i.e. code) it contains.

We encourage you to not copy paste any of the commands from this tutorial in R. Type them out instead. Sure you may make mistakes which will have to be corrected, but that’s the best way to learn. We can guarantee that you will retain this material in your memory far better if you do not take the easy route.

R is an open source, statistical data analysis and visualization program. It is also a computer programming language. There are many proprietary software programs that can be used for statistical data analysis. For example SAS and MATLAB. Most such programs cost money, even though it may or may not go out of your own pocket. These programs are also closed-source meaning that the computer code that is needed to make these programs work is usually a closely held secret and the end users are not privy to it. This stifles innovation.

In contrast, the entire R programming language is open source. Scientists and programmers believe that this allows for and encourages further innovation. Because the code is freely available to anyone, it is constantly being modified and improved. Examples include adding new functionality and removing bugs. You may not do the same with closed source programs.

When you install the R distribution on your computer, it comes with a range of basic functions, enough to perform basic but wide ranging statistical analyses (think ANOVA, T-test etc.) and then visualize the results (think histograms, scatterplots, barplots etc.). This suite of functions is together called the base-R distribution. The latest version of R is 3.6.2. Each version also gets a name. Version 3.6.2 is named Dark and Stormy Night. R was developed by the R Foundation for Statistical Computing located at https://r-project.org, which provides a great deal of information related to R.

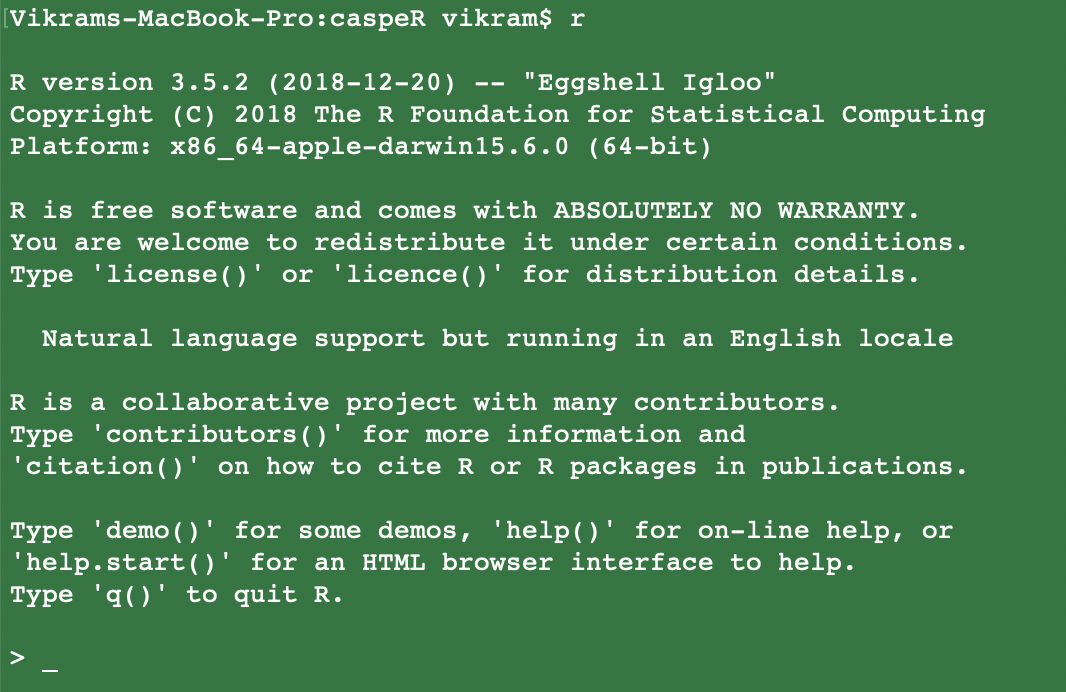

In it’s most simplistic form, R can be run through a termianl which provides the commandline interface. Simply type r on either Linux, Macintosh or Windows inside a terminal (CMD program in Windows) and R will launch.

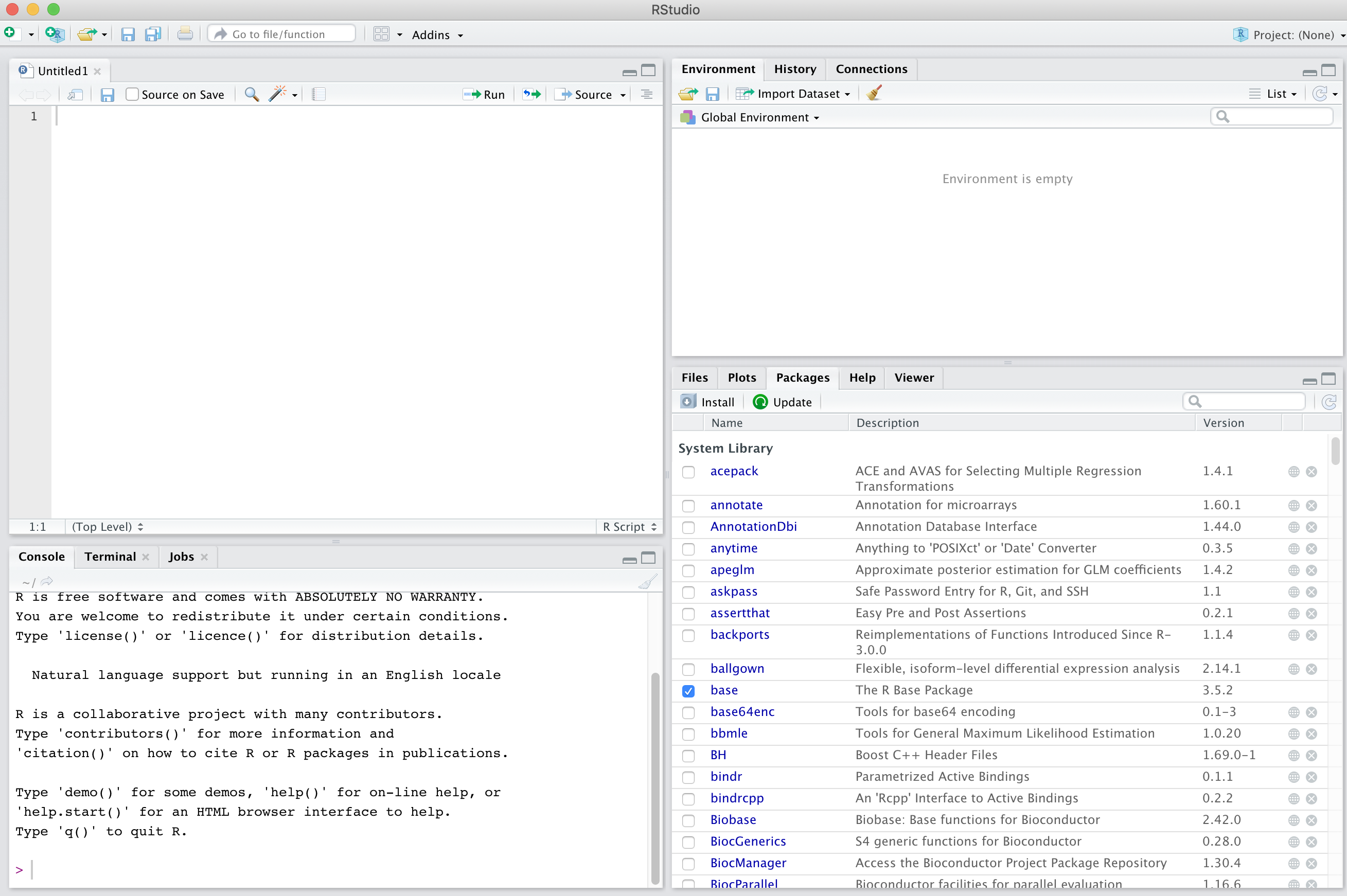

However, not everyone is fond of commandline interfaces. R-Studio exists as a interface bridge between R and you. But that’s not the only thing it does. It is an extremely feature rich GUI program that brings you enhanced functionality to use R.

If you think of R as the backbone then R-Studio provides a graphical user interface to interact with that backbone. When you launch R-Studio, it automatically detects the R software installed on your computer and interfaces with it. Let’s take a look at the R interface to become familiar with it.

Much of the work you will do will do will happen in the two left panes of R-Studio. These are

SOURCE which is where you will write your R commands before executing them and

CONSOLE where the execution happens. The console is the same thing as running R in terminal.

You can always type commands directly in the console without writing them in the source first. This allows you to test commands out. When your workflow begins to get more complex, the source comes in handy.

You will get the hang of R-Studio once we start working through it. The author will explain more features as they become relevant for the task at hand.

We will start with very simple tasks and build on that so that by the end of the day you will have a better idea of what R is capable of.

At a very basic level, R can be used as a calculator, both simple and scientific. When performing calculations, basic rules of Maths apply i.e. PEMDAS

Let’s try some exercises:

Here are the outcomes:

489 * 20

[1] 9780

5222/40.78

[1] 128.053

(32*8) + (1000/5.2)

[1] 448.3077

log(7)

[1] 1.94591

log10(7)

[1] 0.845098

550^2

[1] 302500

sqrt(302500)

[1] 550Much of the work in this environment is done by manipulating objects that are stored in R’s memory. These objects could be something that was created within R or bringing existing data into the environment. In either case, you will need to make use of the assignment operator <- or =. Both are interchangeable. By far in my experience, most people use the first symbol, though nothing says you have to use one of the other. They are fully equivalent.

8 into an object a. Here is another example:As you can see, both objects are now in R’s memory along with their values.

Note: ls is a command for listing objects in the working space. The () you see after that is part of R syntax. Every command in R must end with the paranthesis. Although it’s not being implemented here, usually one passes various arguments or options to the command inside those parentheses.

To check their values, simply type their name at their prompt:

There are many different types of objects that you can store in R’s memory. They can range from very simple numeric objects such as the ones in the examples above, to very complex. The objects can be either singular storing a single number (numeric, or character) or vectors (multiple numbers and/or characters) or large matrices consisting of multiple rows and columns. A typical spreadsheet that we have all worked with in the past is an example of this class of object. Let’s take a look at some moderately complex examples:

Note how the c() or concatenate allows you to create a vector of numbers.

You could have created this exact same vector another way e.g.

As you can see, there are multiple methods for performing same operations. The second one took less effort and is smarter. It also omits the usage of the concatenate function.

Let’s make a character vector

monthsC <- c("January", "February", "March", "April", "May", "June",

"July", "August", "September", "October", "November", "December")

monthsC

[1] "January" "February" "March" "April" "May" "June"

[7] "July" "August" "September" "October" "November" "December" We can perform various functions on the vectors. For example, if the vectors are of equal length, we can combine them together into a data frame.

year <- data.frame(months, monthsC)

year

months monthsC

1 1 January

2 2 February

3 3 March

4 4 April

5 5 May

6 6 June

7 7 July

8 8 August

9 9 September

10 10 October

11 11 November

12 12 DecemberYou will notice that R nicely formats the objects when printing them to the screen. This is quite useful when you are looking at larger data frames.

numdays) containing number of days in each month (assume leap-year) and create a new data frame containing months, monthsC and numdays vectors.In our last example, we created a data frame that is a combination of character and numeric vector. But data frames can also be completely numeric, as in the following example:

jackhighC <- c(-2, 0, 6, 11, 17, 23, 28, 27, 22, 14, 4, -2)

jacklowC <- c(-15, -13, -8, -4, 0, 3, 5, 4, 0, -4, -9, -14)

```r

- Now let's make a numeric data frame with these data:

```r

jacktemp <- data.frame(jackhighC, jacklowC)

jacktemp

jackhighC jacklowC

1 -2 -15

2 0 -13

3 6 -8

4 11 -4

5 17 0

6 23 3

7 28 5

8 27 4

9 22 0

10 14 -4

11 4 -9

12 -2 -14

jacktemp <- data.frame(year, jacktemp)

jacktemp

months monthsC jackhighC jacklowC

1 1 January -2 -15

2 2 February 0 -13

3 3 March 6 -8

4 4 April 11 -4

5 5 May 17 0

6 6 June 23 3

7 7 July 28 5

8 8 August 27 4

9 9 September 22 0

10 10 October 14 -4

11 11 November 4 -9

12 12 December -2 -14

Notice that in above example, we overwrote the original data frame jacktemp by concatenating it with the year data frame. But we retained the original name. We could have stored this new data frame under a new name, but the method we used reduces clutter.

Now let’s convert the temperatures listed in degrees Celsius to degress Fahrenheit. To do this, multiply the tempearature in degC by 9/5, then add the resulting number to 32. For example, if you were converting 4C to Fahrenheight, you would do this:

jacktemp$jackhighF <- (jacktemp$jackhighC * 9/5) + 32

jacktemp

months monthsC jackhighC jacklowC jackhighF

1 1 January -2 -15 28.4

2 2 February 0 -13 32.0

3 3 March 6 -8 42.8

4 4 April 11 -4 51.8

5 5 May 17 0 62.6

6 6 June 23 3 73.4

7 7 July 28 5 82.4

8 8 August 27 4 80.6

9 9 September 22 0 71.6

10 10 October 14 -4 57.2

11 11 November 4 -9 39.2

12 12 December -2 -14 28.4

jacklowC column.So far we saw some of the way to generate data within R. But of course, importing data is an integral part of R functionality. We will look at some simple examples first. R provides functions for reading delimited flat text files i.e. .csv (comma separated) and .txt (tab separated).

census.csv. The .csv extension indicates that this is a comma separated file. So we will employ the R function for reading such files.Notice the use of assignment operator i.e. <- to send information obtained from read.csv and then storing it inside the object called census. This object name is completely arbitrary. You could use any name you wish, so long as the name is not the same as one of the R functions and the other stipulation is that it may not begin with a number.

A quick method for checking what the data in an object looks like is to run the head() function on it. For example,

head(census)

GEO_ID Location Estimate MarginError

1 0400000US27 Minnesota 5527358 *****

2 0400000US28 Mississippi 2988762 *****

3 0400000US29 Missouri 6090062 *****

4 0400000US30 Montana 1041732 *****

5 0400000US31 Nebraska 1904760 *****

6 0400000US32 Nevada 2922849 *****This function will always display the first six rows of the data set. Similarly you can check the last six rows with the tail() function.

tail(census)

GEO_ID Location Estimate MarginError

48 0400000US22 Louisiana 4663616 *****

49 0400000US23 Maine 1332813 *****

50 0400000US24 Maryland 6003435 *****

51 0400000US25 Massachusetts 6830193 *****

52 0400000US26 Michigan 9957488 *****

53 0100000US United States 322903030 *****Notice how R always formats the data nicely such that the columns are perfectly aligned. It also always shows the header line, even when you are looking at the bottom of the file only.

You might want to check the dimensions of this data frame (i.e. number of columns and rows).

The first number is for rows and second for columns. There are 53 rows because in addition to the 50 states, we have data on District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the entire United States.

If you wanted to check data in other columns and rows that are between those shown by head() and tail() functions, R provides multiple ways to do so. R provides a coordinate system as follows:

obj[ROW,COL]

For example, to extract row 20 and columns 1:4, you would type this:

census[20,1:4]

In fact, when asking for all columns in a given row, the column call is superfluous. Instead try this:

census[20,] which will provide the exact same information as above.

census[15:25,]

GEO_ID Location Estimate MarginError

15 0400000US41 Oregon 4081943 *****

16 0400000US42 Pennsylvania 12791181 *****

17 0400000US44 Rhode Island 1056611 *****

18 0400000US45 South Carolina 4955925 *****

19 0400000US46 South Dakota 864289 *****

20 0400000US47 Tennessee 6651089 *****

21 0400000US48 Texas 27885195 *****

22 0400000US49 Utah 3045350 *****

23 0400000US50 Vermont 624977 *****

24 0400000US51 Virginia 8413774 *****

25 0400000US54 West Virginia 1829054 *****There is a single column of numeric data in this data frame. What are some of the questions you can ask of this data? Here are a few I came up with:

We can easily answer these questions using functions in R. However, our data set currently has a row containing combined numbers for all states and territories. We can either remove that row entirely, or better yet, make a copy of this data frame without the last row. Here is how to do it:

census2$Location

[1] Minnesota Mississippi Missouri

[4] Montana Nebraska Nevada

[7] New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico

[10] New York North Carolina North Dakota

[13] Ohio Oklahoma Oregon

[16] Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina

[19] South Dakota Tennessee Texas

[22] Utah Vermont Virginia

[25] West Virginia Washington Wisconsin

[28] Wyoming Puerto Rico Alabama

[31] Alaska Arizona Arkansas

[34] California Colorado Connecticut

[37] Delaware District of Columbia Florida

[40] Georgia Idaho Hawaii

[43] Illinois Indiana Iowa

[46] Kansas Kentucky Louisiana

[49] Maine Maryland Massachusetts

[52] Michigan

subset(census2, Estimate == 581836)

GEO_ID Location Estimate MarginError

28 0400000US56 Wyoming 581836 *****There are a few housekeeping tasks you will need to do maintain your R installation on a regular basis. This involves keeping your base-R version, R-Studio installation as well as various additional packages updated. Installing a new version of R often breaks existing packages, which would then have to be updated as well. Updating the R installation is as simple as going to r-project.org and downloading/installing the latest version. Unfortunately given the administrative permissions on the workstations you are working on right now, we can’t really try this out. However, we will tackle the subject of packages next.

Some of you might be wondering what an R package is? It’s a fair question that baffles many beginner R users. Remember that we talked earlier about base-R distribution, which includes a core set of functions to work with data. We visited some of these functions above. But R is now used in a large number of disparate scientific fields scattered across industry, academic, government and non-government entities. This means need for highly specialized functions to do specific tasks that are not included in your base-R distribution.

A R package is simply a collection of functions that perform specialized tasks. Data scientists and enthusiasts alike volunteer their valuable time to develop such specialized packages and then make them avaialble to the larger user base free of charge.

We can think of an analogy here. Your smartphone operating system comes with a suite of basic functions that allow your to make and receive phone calls and text messages. However, if you need to do a video chat, you will need a special app for that. To check your email, you will need another app. An app here is highly similar to a package capable of doing specific tasks.

There are literally thousands of R packages available. To give you a few example:

ggplot2 is used extensively in data visualizationvegan is a package that contains a larger number of statistical testsRMarkdown allows generation of dynamic documents such as the one you are currently readingParallel splits data analysis jobs into chunks so they can be completed faster by multiple processorsSo on and so forth.

You can download and install packages from several sources, though of course not all packages are avaialble from all sources. These sources are also called as repositories. There are three main repositories that you should be aware of:

CRAN: The Comprehensive R Archive Network located at CRAN.r-project.org: This is by far the biggest and most vetted repository of packages that are available. Before a package appears in the CRAN repository, it must be submitted for review and thoroughly vetted and approved by the folks responsible for CRAN. As of today, there are 15,364 packages available there.

Bioconductor: Is the repository to go to if you are looking for biological analysis software e.g. bioinformatics packages. This repository is located at bioconductor.org and currently contains 1,823 packages.

GitHub: has become the de-facto place to share cutting edge developments for many of the packages available on the above two repositories. Often times when package installation fails due to incompatibility between the R version and the package, you can find the source code for the package on this repository and circumvent the compatibility problems associated with pre-compiled packages. It’s too difficult to count the number of package sources available on GitHub. But it will be easy to find what you need when you need it.

There are several ways of installing R packages:

install.packages(). For example, let’s try installing one:When you launch this command for the first time, a dialogue box will pop out on your screen asking you to choose a mirror for installation. What is a mirror you might ask? Because R packages are installed from all over the world, repositories make their packages available on a number of web servers (called a mirror here) around the world. The idea is that by choosing a mirror closest to you, the download speeds would be the highest you can get.

If the above command was successful, the package was installed. However, that doesn’t automatically make the package functions available for your use. You must first load the package in R’s memory. Here is how to do it:

Note how we used quotes around the package name when installing it but not when loading it. If you deviate from this convention, R will generate an error message.

DESeq2. If you go the package webpage, you will find an installation section. It consists of two separate commands:This loads the script called BiocManager on your computer, which is needed for installation of every bioconductor package. Next, install the package:

There are two circumstances under which you will need to access package source code on GitHub. One scenario is that your R version is incompatible with the package you are trying to install from CRAN. Alternatively, you may find that the package version on CRAN is outdated and you want access to new functionality included only in the source code available on GitHub. In either of these cases, here is how to install an R package from source:

First, you will need a package called devtools

devtools first. But assuming this worked, let’s install a package called RMarkdown.rstudio part is the name of the author/account on GitHub and rmarkdown is the name of the package.Install the tidyverse family of packages from GitHub. Their address is: github.com/hadley/tidyverse.

R-Studio provides a nice interface for accessing help documentation within R, but you can also search for help through the console window. Invoking help pages for any function is done by simply typing the name of the function preceded by a question mark. Try the following out.

R has become extremely popular as a powerful statistical analysis program in all sectors e.g. academics, industry, government and NGOs. Consequently, there are a number of websites, forums and mailing lists that are available to you. When you run into a problem with your code and any R function, chances are that someone has already asked a question about it which has been answered. Below is a list of resources that you might find helpful.

R provides numerous functions for performing statistical analysis on a wide variety of data sets. In this section, We will both import example data and also create some on the fly within R.

Here we will look at some of the most commonly used summarizing statistics:

mtcars

?mtcars

mtcars package:datasets R Documentation

Motor Trend Car Road Tests

Description:

The data was extracted from the 1974 _Motor Trend_ US magazine,

and comprises fuel consumption and 10 aspects of automobile design

and performance for 32 automobiles (1973-74 models).

Usage:

mtcars

Format:

A data frame with 32 observations on 11 (numeric) variables.

[, 1] mpg Miles/(US) gallon

[, 2] cyl Number of cylinders

[, 3] disp Displacement (cu.in.)

[, 4] hp Gross horsepower

[, 5] drat Rear axle ratio

[, 6] wt Weight (1000 lbs)

[, 7] qsec 1/4 mile time

[, 8] vs Engine (0 = V-shaped, 1 = straight)

[, 9] am Transmission (0 = automatic, 1 = manual)

[,10] gear Number of forward gears

[,11] carb Number of carburetors

min(mtcars$mpg)

[1] 10.4

subset(mtcars, mpg == 10.4)

mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

Cadillac Fleetwood 10.4 8 472 205 2.93 5.250 17.98 0 0 3 4

Lincoln Continental 10.4 8 460 215 3.00 5.424 17.82 0 0 3 4

subset(mtcars, mpg == 33.9)

mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

Toyota Corolla 33.9 4 71.1 65 4.22 1.835 19.9 1 1 4 1

subset(mtcars, mpg < 21 & mpg > 19)

mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

Merc 280 19.2 6 167.6 123 3.92 3.440 18.30 1 0 4 4

Pontiac Firebird 19.2 8 400.0 175 3.08 3.845 17.05 0 0 3 2

Ferrari Dino 19.7 6 145.0 175 3.62 2.770 15.50 0 1 5 6

summary(mtcars)

mpg cyl disp hp

Min. :10.40 Min. :4.000 Min. : 71.1 Min. : 52.0

1st Qu.:15.43 1st Qu.:4.000 1st Qu.:120.8 1st Qu.: 96.5

Median :19.20 Median :6.000 Median :196.3 Median :123.0

Mean :20.09 Mean :6.188 Mean :230.7 Mean :146.7

3rd Qu.:22.80 3rd Qu.:8.000 3rd Qu.:326.0 3rd Qu.:180.0

Max. :33.90 Max. :8.000 Max. :472.0 Max. :335.0

drat wt qsec vs

Min. :2.760 Min. :1.513 Min. :14.50 Min. :0.0000

1st Qu.:3.080 1st Qu.:2.581 1st Qu.:16.89 1st Qu.:0.0000

Median :3.695 Median :3.325 Median :17.71 Median :0.0000

Mean :3.597 Mean :3.217 Mean :17.85 Mean :0.4375

3rd Qu.:3.920 3rd Qu.:3.610 3rd Qu.:18.90 3rd Qu.:1.0000

Max. :4.930 Max. :5.424 Max. :22.90 Max. :1.0000

am gear carb

Min. :0.0000 Min. :3.000 Min. :1.000

1st Qu.:0.0000 1st Qu.:3.000 1st Qu.:2.000

Median :0.0000 Median :4.000 Median :2.000

Mean :0.4062 Mean :3.688 Mean :2.812

3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:4.000 3rd Qu.:4.000

Max. :1.0000 Max. :5.000 Max. :8.000

Load the data on approval ratings of U.S. presidents since 1945 through 1975. The dataset is named presidents.

Examine the data structure (hint: head, tail etc.)

Analyze a summary of each variable in the data set

rnorm(10, 0, 1)

[1] -0.07464322 -1.51165519 0.24215035 -1.01457525 0.12778428 -0.39497391

[7] -1.98659094 -0.01535476 -1.90261294 0.76944419Here we are using the function rnorm() which takes three arguments:

rnorm(length, mean, sd)In the above example, we asked for length=10, mean=0 and sd=1.

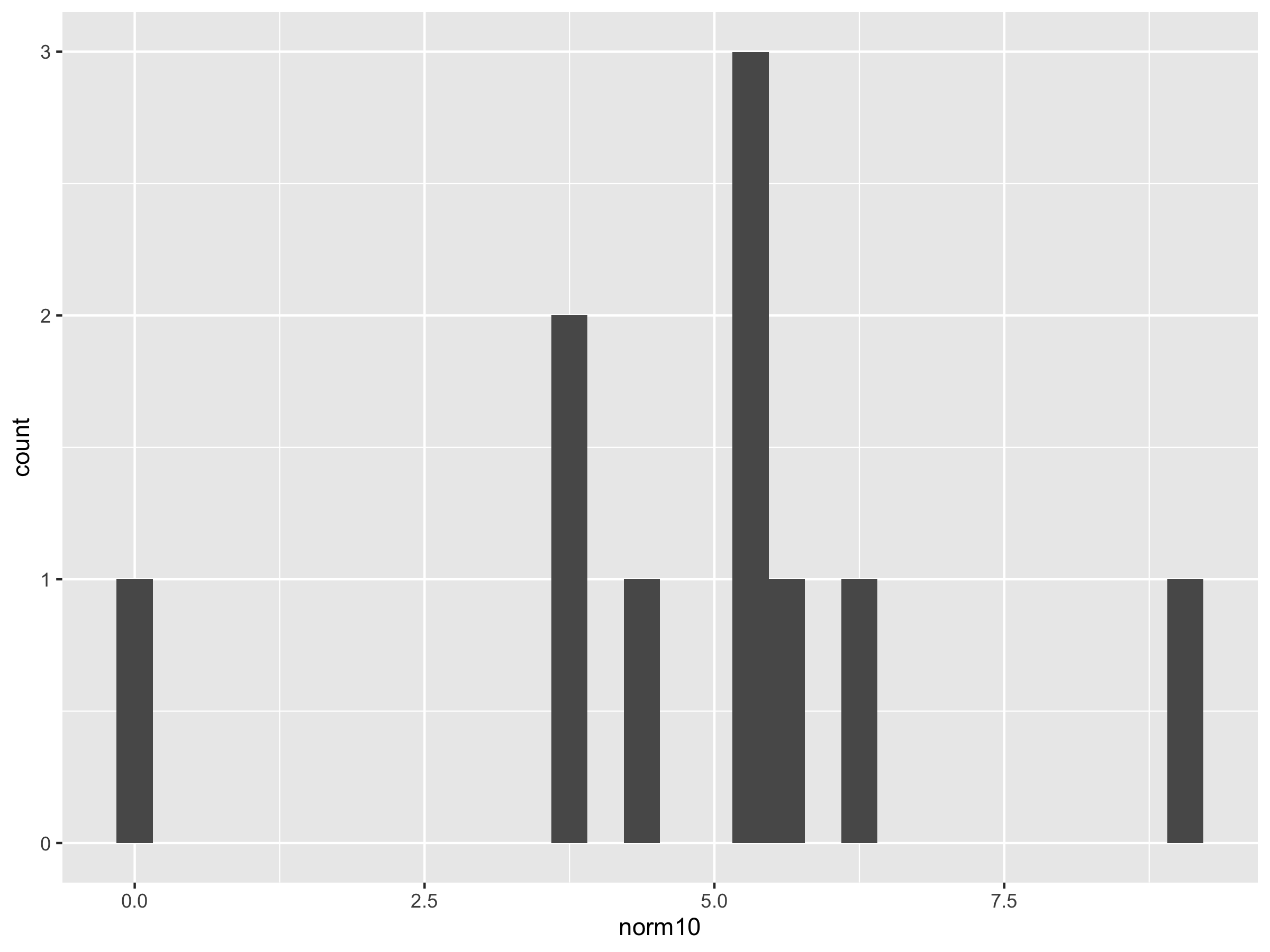

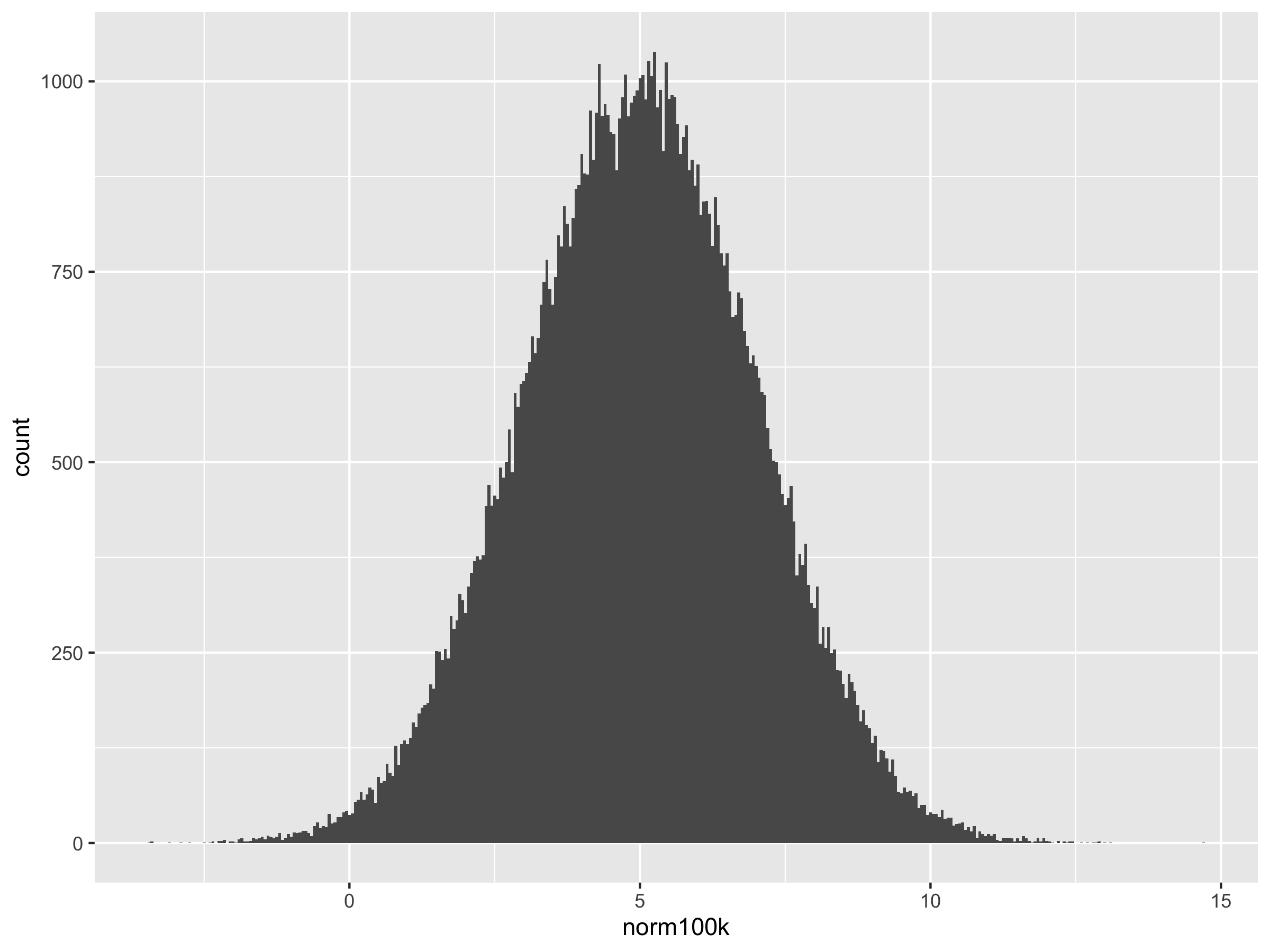

Let’s create 4 additional vectors of variable length all with a mean of 5 and standard deviation of 2.

norm10 <- rnorm(10, 5, 2)

norm100 <- rnorm(100, 5, 2)

norm1k <- rnorm(1000, 5, 2)

norm100k <- rnorm(100000, 5, 2)

ggplot() + geom_histogram(aes(norm100))

ggplot() + geom_histogram(aes(norm1k))

ggplot() + geom_histogram(aes(norm100k))

The R function which deals with Uniform Distribution is named runif. Look at the help page for it.

Simulate two vectors, one of length 100 and another of 1 million and store them in different objects.

Draw a histogram of each vector to examine the shape of the distribution and identify any differences.

It is possible to randomly sample data from a distribution. The sample() function takes two arguments.

sample(vector, n, replace=VALUE)

Where vector = distribution, n = size of your sample

replace can be set to either TRUE or FALSE depending upon whether your experiment allows re-sampling of the same value across successive iterations. However, it must be set to TRUE if your sample size exceeds the size of the vector. In other words, if you are sampling a vector of length 10, fifteen times, you will run out of numbers if replace was set to FALSE. Try the following example:

sample(1:10, 15, replace=FALSE)

Error in sample.int(length(x), size, replace, prob) :

cannot take a sample larger than the population when 'replace = FALSE'

sample(1:10, 15, replace=TRUE)

[1] 7 3 10 4 5 3 5 7 10 3 10 1 2 4 2

sed.seed(5)

sample(500:1000, 50, replace=TRUE)

[1] 821 862 684 706 702 876 796 712 721 570 902 886 793 813 930 808 831 515 909

[20] 984 627 526 956 969 719 829 584 621 973 806 612 937 683 591 768 962 906 734

[39] 553 929 645 963 691 652 893 797 615 747 507 967Seed can be set to any number you wish. Using the same seed again will reproduce your original sample. Try running the command again with the same seed to verify.

Now draw the sample again without setting the seed and you will notice that it changes again.

sample(500:1000, 50, replace=TRUE)

[1] 719 903 864 990 603 735 944 622 962 825 648 590 854 571 550 933 579 919 507

[20] 980 965 831 815 880 589 626 724 514 873 599 708 647 624 741 638 636 503 502

[39] 911 654 726 503 526 739 668 921 629 771 904 687The set.seed() function is extremely useful for achieving reproducibility. You may use it with any function in R, not just sample.

Sample function works both with numerical and character data. Let’s consider an example from genetics. Imagine you wish to create a population of 200 individuals to to study a gene A. This gene appears in the population in 2 forms: A and a. Because all the individuals have two sets of genes (hence called diploid), there are three distinct possibilities for the genetic makeup of each individual:

AA or Aa or aa

pop <- sample(c("AA", "Aa", "aa"), 200, replace=TRUE)

pop

[1] "AA" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "Aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "Aa" "AA" "aa"

[16] "Aa" "AA" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "Aa" "Aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "aa" "AA" "aa"

[31] "Aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "Aa" "AA" "Aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "AA" "AA"

[46] "aa" "Aa" "aa" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa"

[61] "aa" "aa" "Aa" "AA" "aa" "Aa" "AA" "aa" "aa" "AA" "aa" "AA" "Aa" "AA" "AA"

[76] "AA" "aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "AA" "Aa"

[91] "aa" "AA" "aa" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "AA" "AA" "aa" "aa" "aa"

[106] "Aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "Aa" "aa" "Aa" "Aa" "aa" "AA" "aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "aa"

[121] "AA" "Aa" "AA" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "AA" "aa" "Aa"

[136] "Aa" "AA" "aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "Aa" "AA" "Aa" "AA" "AA"

[151] "aa" "AA" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "Aa" "Aa"

[166] "AA" "AA" "aa" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "Aa" "AA" "Aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "AA"

[181] "aa" "AA" "Aa" "AA" "Aa" "Aa" "Aa" "AA" "Aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "Aa"

[196] "Aa" "AA" "AA" "AA" "aa"

pop1 <- sample(pop, 50, replace=TRUE)

pop1

[1] "aa" "AA" "AA" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "AA" "aa" "AA" "Aa" "aa" "AA" "aa" "Aa" "Aa"

[16] "Aa" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "Aa" "AA" "aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "aa" "aa"

[31] "Aa" "Aa" "aa" "AA" "AA" "Aa" "Aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "aa" "Aa" "aa" "aa"

[46] "Aa" "aa" "aa" "AA" "AA"

sum(pop1 == "AA")

[1] 13

sum(pop1 == "Aa")

[1] 14

sum(pop1 == "aa")

[1] 23

airquality data set from New York City.

data(airquality)

dim(airquality)

[1] 153 6

head(airquality)

Ozone Solar.R Wind Temp Month Day

1 41 190 7.4 67 5 1

2 36 118 8.0 72 5 2

3 12 149 12.6 74 5 3

4 18 313 11.5 62 5 4

5 NA NA 14.3 56 5 5

6 28 NA 14.9 66 5 6From a character vector containing HEADS and TAILS, randomly take a sample of length 1000.

Count how many HEADS were sampled.

When analyzing any type of data, you may encounter the need for repetition, where a given task needs to be repeated a number of times. If you need to repeat just a handful of times, then you can afford to run it manually. If even 10 repetitions are needed, you would save a lot of time by automating these tasks through loops. A very popular type of loop is called a for() loop. Some programmers will argue that loops are very slow to operate, but this really isn’t a concern when repeating smaller tasks. Let’s look at some examples:

for (i in 1:20){

print(i)

}

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

[1] 7

[1] 8

[1] 9

[1] 10

[1] 11

[1] 12

[1] 13

[1] 14

[1] 15

[1] 16

[1] 17

[1] 18

[1] 19

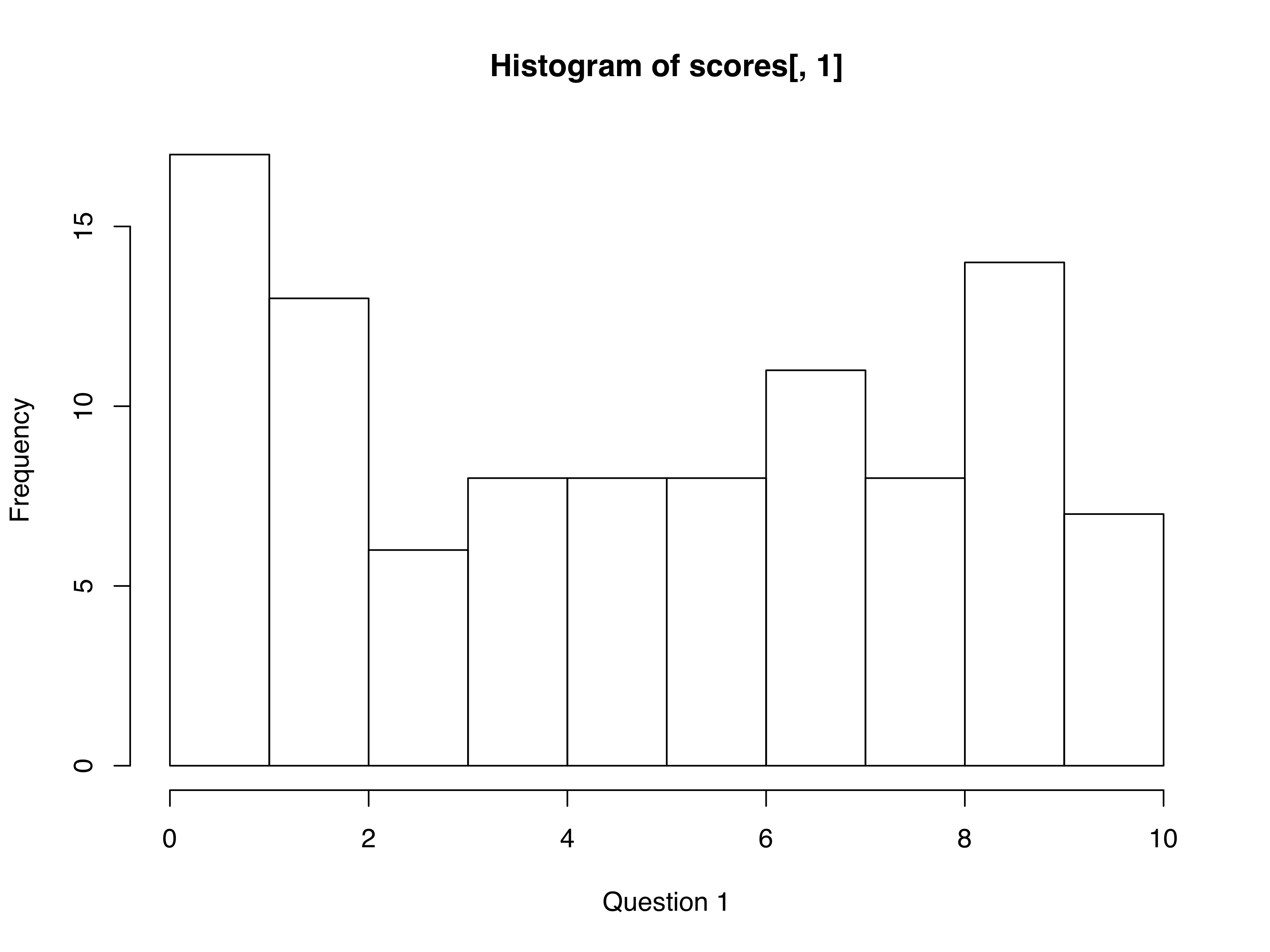

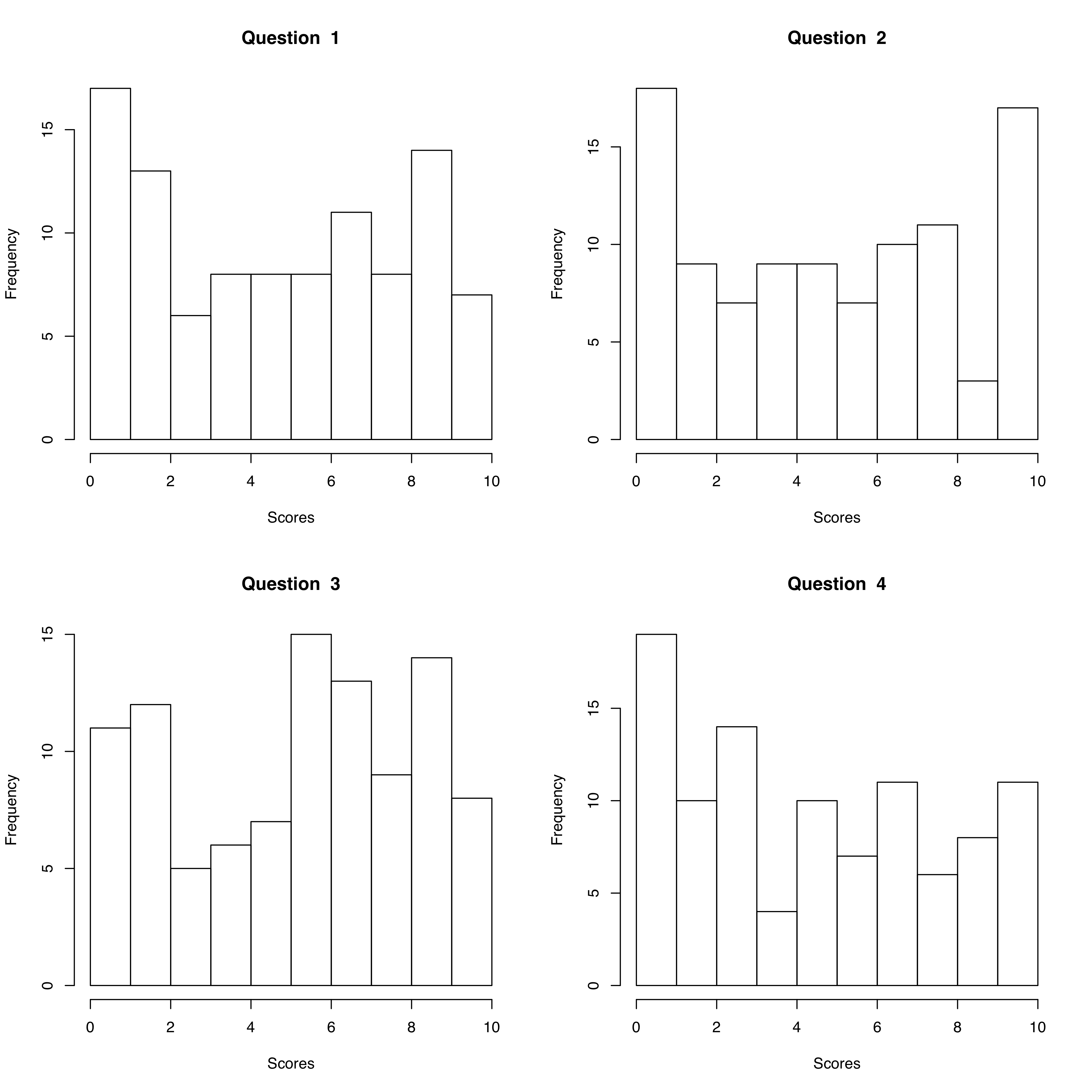

[1] 20for() loops are also commonly used when generating a number of similar plots from the same data set. Consider a data set where exam scores are recorded for 200 students. Each student has to answer four questions and their grade for each question ranges between 0 and 10. First, let’s creat this data within R using the sample function.

Generate 100 integers between 0 and 10 with replacement.

sample(0:10, 100, replace=TRUE)

[1] 10 6 3 2 5 3 10 10 1 2 10 9 8 10 7 3 8 1 4 9 10 4 3 3 6

[26] 10 8 2 9 7 1 10 0 4 0 3 10 5 6 2 8 8 5 4 8 9 5 10 5 7

[51] 6 5 9 9 0 10 10 9 7 5 0 0 6 4 5 9 2 10 9 1 5 2 2 7 10

[76] 7 6 4 3 7 6 5 2 10 10 4 4 9 0 2 8 1 1 5 0 3 3 8 2 5

replicate(4, sample(0:10, 100, replace=TRUE))

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 8 4 1 0

[2,] 7 2 8 10

[3,] 1 5 5 1

[4,] 10 7 7 1

[5,] 8 1 0 0

[6,] 0 2 4 5

[7,] 6 9 10 9

[8,] 9 4 9 6

[9,] 2 0 10 5

[10,] 9 0 5 9

[11,] 5 7 2 9

[12,] 9 6 7 2

[13,] 8 9 7 3

[14,] 3 10 8 0

[15,] 0 3 4 10

[16,] 9 7 4 8

[17,] 7 9 1 3

[18,] 3 6 10 1

[19,] 3 0 7 5

[20,] 5 5 10 10

[21,] 3 10 8 1

[22,] 6 0 10 5

[23,] 4 1 4 8

[24,] 7 1 4 10

[25,] 5 8 1 6

[26,] 10 3 2 9

[27,] 7 8 0 8

[28,] 2 4 2 5

[29,] 4 9 7 6

[30,] 4 5 9 0

[31,] 3 10 8 2

[32,] 1 2 8 2

[33,] 7 10 5 8

[34,] 5 5 0 7

[35,] 8 6 10 9

[36,] 2 0 4 6

[37,] 1 6 5 7

[38,] 10 5 10 4

[39,] 7 3 4 5

[40,] 9 6 8 10

[41,] 1 3 1 8

[42,] 8 4 5 8

[43,] 1 5 8 7

[44,] 3 3 0 10

[45,] 1 4 8 1

[46,] 4 6 4 5

[47,] 7 10 8 5

[48,] 9 3 1 0

[49,] 3 0 5 2

[50,] 1 9 9 6

[51,] 6 5 4 1

[52,] 4 7 0 9

[53,] 1 9 10 0

[54,] 5 3 6 6

[55,] 9 2 7 8

[56,] 7 10 7 5

[57,] 5 10 7 10

[58,] 10 5 9 6

[59,] 6 4 1 4

[60,] 2 2 6 10

[61,] 3 8 3 5

[62,] 2 1 4 4

[63,] 10 1 8 5

[64,] 10 0 3 2

[65,] 6 5 0 1

[66,] 9 4 7 1

[67,] 6 9 5 5

[68,] 8 8 9 8

[69,] 4 8 1 0

[70,] 4 5 3 0

[71,] 5 8 0 5

[72,] 3 3 0 10

[73,] 0 10 7 3

[74,] 1 5 0 5

[75,] 6 6 5 9

[76,] 2 3 5 7

[77,] 8 7 9 3

[78,] 9 5 2 10

[79,] 0 7 3 6

[80,] 0 0 10 3

[81,] 7 3 1 10

[82,] 9 4 10 6

[83,] 1 9 7 5

[84,] 2 8 5 1

[85,] 3 5 10 8

[86,] 4 5 0 10

[87,] 4 9 8 8

[88,] 2 1 3 9

[89,] 3 0 2 8

[90,] 6 8 6 5

[91,] 4 6 9 0

[92,] 2 7 2 2

[93,] 2 0 4 10

[94,] 2 7 7 8

[95,] 8 0 9 0

[96,] 0 1 10 7

[97,] 10 7 6 2

[98,] 1 4 3 7

[99,] 0 2 6 7

[100,] 9 0 2 8That’s 100 rows (i.e. 100 students) and 4 scores.

Now you want to make histograms for each of these four scores to get a visual of how the class performed on the exam overall.

Before making the loop, first make one histogram:

par(mfrow=c(2,2))

for (i in 1:4){

x <- scores[,i]

hist(x,

main = paste("Question ", i),

xlab = "Scores",

xlim = c(0,10))

}

Load the U.S. states data (data(state)) and check the data frame called state.x77.

Modify the loop above to plot two histograms from this data frame, one each for population and Area.

Also called just the T-test is used to compare mean values of two samples that are assumed to be normally distributed. T-test is a parametric test. The goal is to test whether means of two samples are significantly different from each other.

t.test(x, y)

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: x and y

t = 1.0993, df = 1998, p-value = 0.2718

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.03860205 0.13706775

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

-0.02702567 -0.07625852

x and y are not significantly different from each other (P-value 0.2718).

a <- rnorm(1000, mean=2)

b <- rnorm(1000, mean=4)

t.test(a, b)

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: a and b

t = -44.009, df = 1997.8, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-2.073730 -1.896795

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

2.023478 4.008740 Generate two normally distributed vectors, both with a mean of 0.8.

Compare their with the T-test and observe whether they have similar or different means.

This test is done to test how observed values fit to expectations based on principles. In other words it’s a goodness of fit test. Let’s do an example from population genetics. There is a fundamental theorem in population genetics called the Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium. HWE for short provides for expected proportions of genotypes in a population if it conforms to certain assumptions. We do not need to get into these assumption.

Consider a population of 5000 diploid individuals in which we are studying a gene named F, which has two morphs/alleles/forms: F and f.

Because the organism is diploid, each individual has two copies of this gene (by way of having two chromosomes of each type.

Therefore we have three possible types of individual genotypes at this gene: FF, Ff and ff

HWE posits that genotypic frequencies will add up to unity if the population conforms to certain assumptions.

We can use chi square test to check whether our sampled population is in HWE for gene F.

First, let’s sample a population

p <- (sum(pop == "FF")*2 + sum(pop == "Ff"))/10000

q = (sum(pop == "ff")*2 + sum(pop == "Ff"))/10000

We can estimate Expected genotypic frequencies based on allele frequencies

In contrast, our observed numbers for the same genotypes are: 1726, 1648 and 1626.

Now we can set up the Chi Square Test

| Geno | obs | exp | (O-E)^/E |

|---|---|---|---|

| FF | 1726 | 1289.304 | 147.9119 |

| Ff | 1626 | 2499.392 | 305.1997 |

| ff | 1648 | 1211.304 | 157.6557 |

| Total | 5000 | 5000 | 610.7673 |

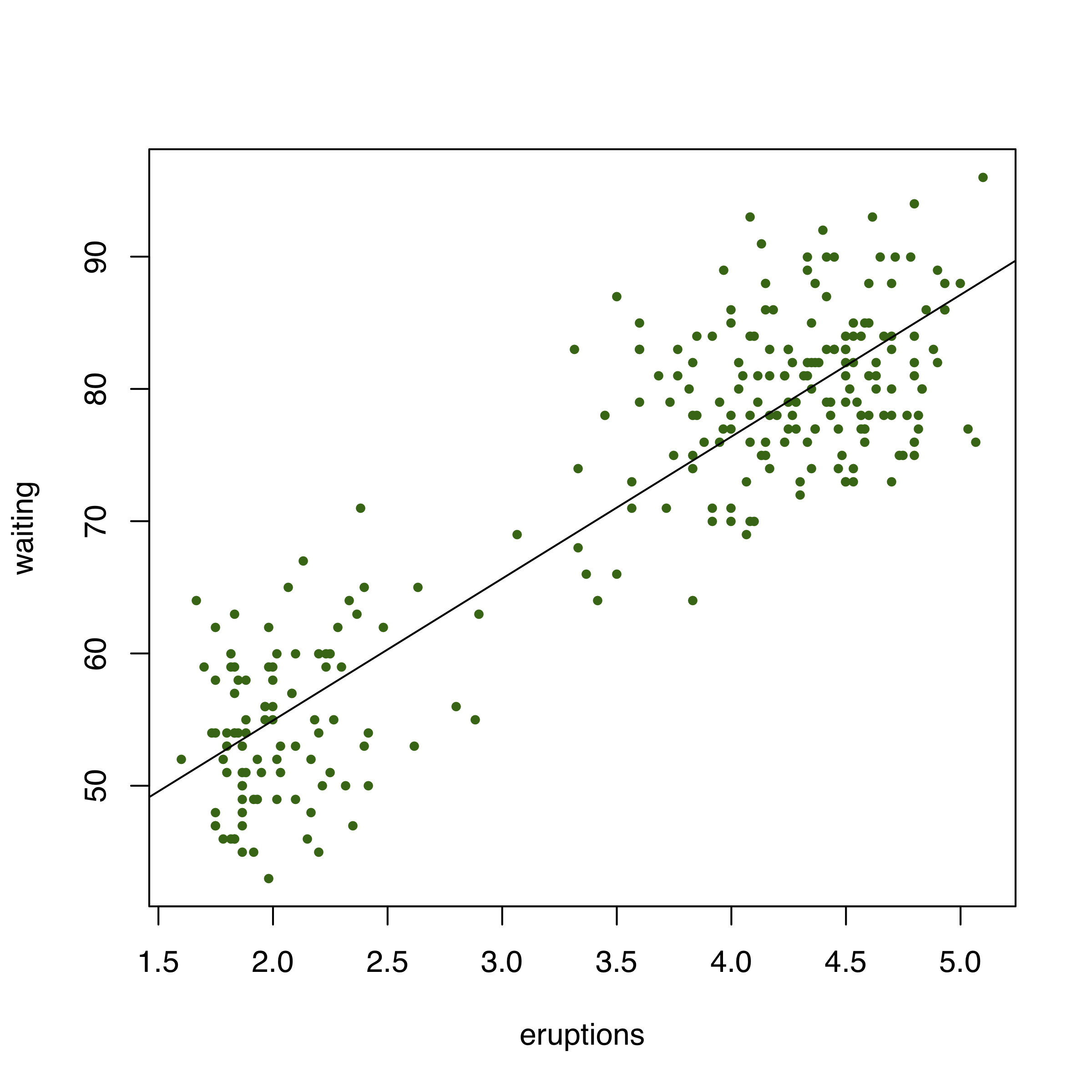

Testing for correlation between two variables is done through multiple functions in R. But not all of them provide significance testing. We will use the function cor.test which provides significance values for the correlation tests and it also allows us to test with different methods e.g. Spearman vs Pearson.

We will use the Faithful dataset built into R, which has eruption duration and wait times between eruptions for the Old Faithful geyser in Yellowstone NP.

data(faithful)

attach(faithful)

cor.test(eruptions, waiting)

Pearson's product-moment correlation

data: eruptions and waiting

t = 34.089, df = 270, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

0.8756964 0.9210652

sample estimates:

cor

0.9008112

cor.test(eruptions, waiting, method="Spearman")

Spearman's rank correlation rho

data: eruptions and waiting

S = 744659, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true rho is not equal to 0

sample estimates:

rho

0.7779721 Thus, there is highly significant correlation between the wait time and eruptions at this geyser.

What does this relationship look in a plot?

Load the state data set you used earlier.

Estimate correlation between high school graduation status and income using both Spearman and Pearson methods

Make a plot of this relationship and draw a regression line